In the face of systemic occupation and oppression, APC member 7amleh - The Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media has been documenting digital rights violations of Palestinians and supporters of Palestinian rights on social media and online spaces.

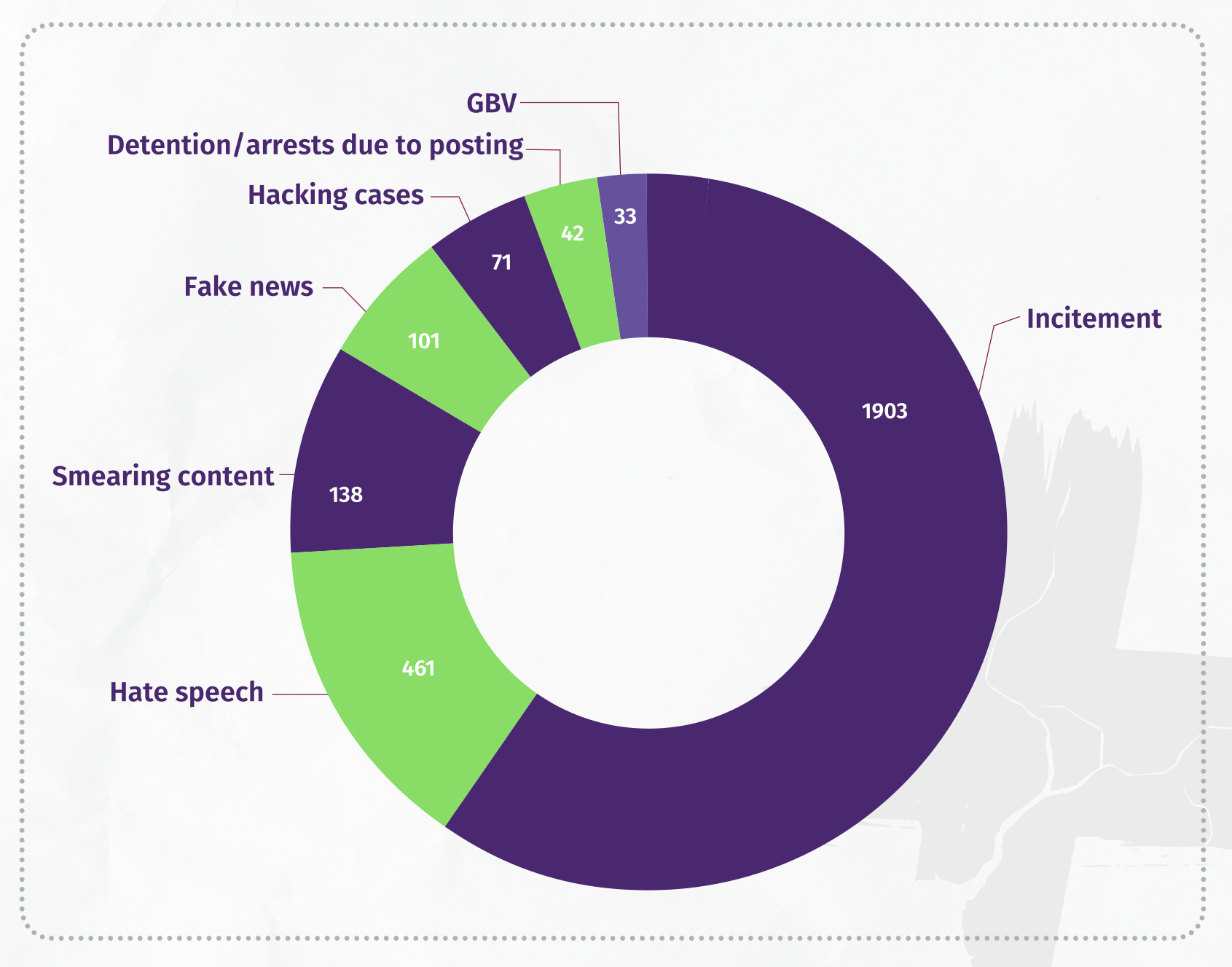

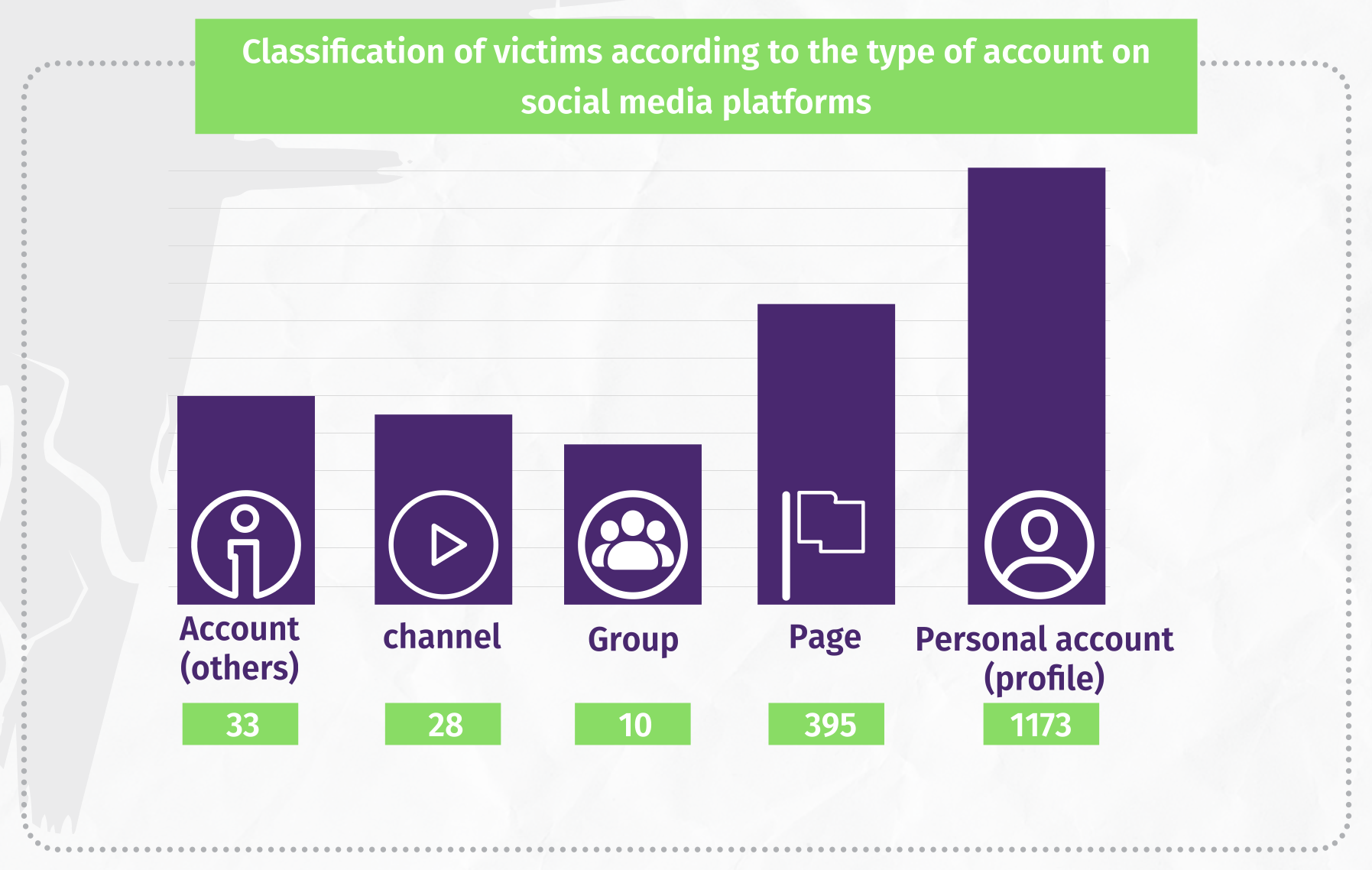

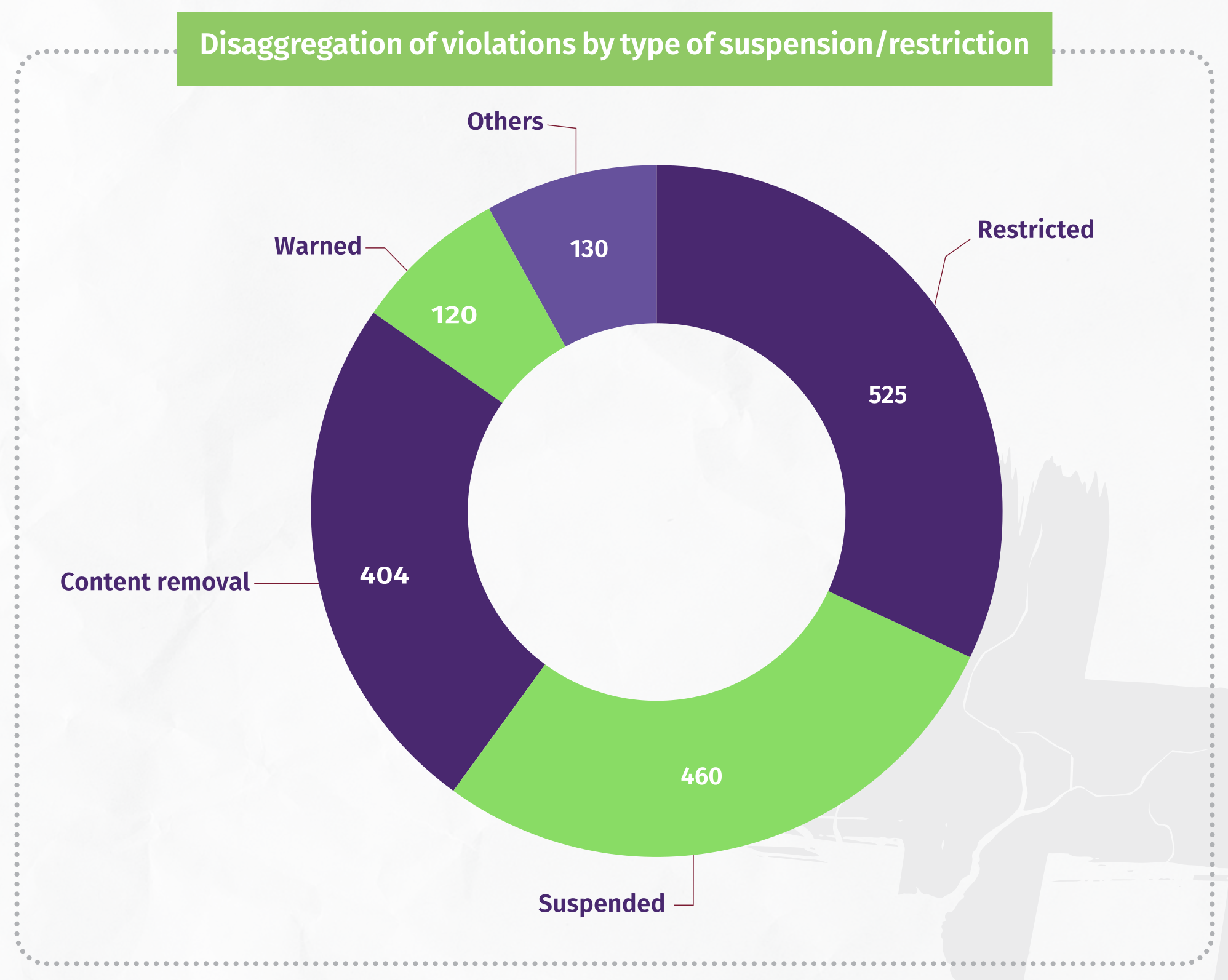

In their new annual report, Hashtag Palestine 2023, 7amleh documents how censorship of Palestinian narratives and content is rampant alongside incitement and hate speech against Palestinians. Using data collected through 7or, their custom platform for tracking digital rights violations, the report analyses the impact of policies that disproportionately target Palestinians, often leading to arrest and persecution. It outlines a powerful set of recommendations to address digital challenges, advocating for a multistakeholder approach by states, companies and civil society to ensure digital safety and security for Palestinians.

We spoke with Ahmad Qadi, head of 7amleh’s monitoring and documentation department, to discuss their latest report and why exposing digital rights violations, censorship and skewed policies is more urgent than ever.

What does the report cover and which aspects would you like to continue working on?

Last year was hectic indeed and we have been working day and night for months to follow up on everything. The report was a very brief overview of what's going on in the digital space. In our report, we comprehensively outlined the significant updates in digital rights over the past year. We presented our data and conducted a thorough analysis of violations documented by 7amleh. We addressed pertinent issues ranging from deliberate internet outages and censorship to the dissemination of violent content.

It would be powerful to analyse and to align the responses of companies to our escalations. We now have thousands of cases where we can assess how companies’ policies apply to the escalations. This gives us powerful insight and also a space to make our position stronger in terms of advocacy for policy change. We have quantitative data, but now we are analysing the qualitative data and we’ll find many insights regarding social media companies' policies.

7amleh developed a powerful platform to track human rights violations online, revealing the disproportionate persecution of Palestinians and supporters and the dire consequences faced by users, activists and journalists. Tell us more about this tool and its significance in Palestinians’ fight for freedom of expression.

We launched the 7or platform, the Palestinian Observatory of Digital Rights Violations, at the beginning of November 2021. It is an internet database and a tool for people to report violations. In Arabic, 7or is an acronym for digital rights, and it also means freedom. It is mainly a data visualisation tool, analysis section and submission tool.

We have developed the 7or platform several times since it launched and recently developed an AI language model in-house to depict this violence. It scrapes data from several social media platforms and automatically classifies it as violent or non-violent content. This way we detect millions of content samples. There is also the manual work in which we receive cases through 7or. These are full cases where we request detailed information such as user, links and screenshots to be able to verify them. We send the cases to the relevant companies and request either the removal of violent content or the restoration of any page or content that’s removed incorrectly.

Since then we have been focusing not only on censorship, like restrictions and disabling accounts, but also on Israeli or Hebrew incitement against Palestinians, because they are related. To give a concrete example, Meta invested a lot in Arabic content moderation, so content in Arabic that's considered violent is removed immediately. We have documented a lot of Arabic content that is not related to violence being removed, such as content criticising Israeli policies or exposing what's going on on the ground.

On the other hand, Meta failed to prove the effectiveness of its content moderation on Hebrew language. According to our assessment, they don’t have an effective content classifier in Hebrew, so this is why we find violent content in Hebrew is rampant and not moderated. We started focusing on this difference to compare policies, and this is why one of our main recommendations is that we need just and fair content moderation policies for all languages.

So you are engaging with social media companies like Meta directly?

We are trusted partners with Meta, X (previously Twitter), YouTube, TikTok and many social media companies. We go to them and tell them, “See, this is content that is violent and you let it out so you should remove it. And this content is just media coverage and you should restore it.” This is the policy side of the content, as content is mostly removed due to policies.

Do you still need some human oversight over the data that's collected? How do you determine what kind of content is being analysed?

We have been reviewing thousands of content samples; we can't review hundreds of thousands but we are retraining the model to be able to raise the accuracy score. We also check against other open source and paid models to verify our classification so that our results are accurate. We are now in the final stages of developing an Arabic classifier so we’ll be able to not only report on Hebrew violence but also Arabic violence.

It requires a lot of technological work and at the same time creating definitions isn’t easy. There is good literature on what is violent content, incitement and smear campaigns, but there is no consensus. In our case what is relevant is that there is an occupation and this violence online in many cases leads to physical attacks. Recently, for example, Israeli-Palestinians have been smeared across social media platforms by Israeli users and hundreds of them have been arrested or dismissed from academic institutions or work for things they posted. There is no legal framework that takes into consideration the rights of Palestinians. I know a Palestinian woman who recently posted how happy she was about her engagement, and she was arrested. This was after 7 October. A girl posted about shakshuka, a national dish, and was arrested because it was interpreted that she was symbolising Palestinians. A teacher was dismissed from school simply because she followed a pro-Palestinian rights account. This is important to focus on: it’s not just attacks online, it also entails real-world consequences.

A lot of Palestinians, especially human rights defenders, have stopped posting anything. These attacks are a way of silencing freedom of expression.

There a lot of excellent recommendations at the end of 7amleh’s report. Is there one area where you think it is particularly urgent for people to focus their attention?

Governments around the world should press companies to comply with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. This is basic – no one can deny or refuse such principles and we need to regulate the use of spyware technologies in the context of Palestine.

On social media we requested just, fair and transparent use of content moderation policies. Half of the world’s population uses social media and you cannot allow select narratives and oppress others. In the context of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and other conflicts, we need to be able to lead dialogues online and to allow victims to express themselves. We need transparency in these policies and request that companies not respond so easily to government requests when something feeds into their censorship definitions. Israel says that around 90-95% of their requests to remove content are met by social media companies but the companies themselves do not disclose this information. We need a free, fair ability to discuss online what's going on and of course to remove any violent content in any language, and understand these equally.

Are there specific recommendations that could have immediate impact and are relatively attainable right now?

In the context of Palestine, Meta’s platforms are widely used by Palestinians and Meta is one of the top companies that censor Palestinian content. Meta could easily and simply adhere to the recommendations by the BSR due diligence report, in which they admitted that there is over-moderation in Arabic and under-moderation in Hebrew. We requested the development of functioning and effective Hebrew hostile language classifiers, because this incitement and smearing online that we have seen in the last few months has a direct impact on Palestinians’ lives. Meta said that they have developed it and it is functioning but that it’s not fully effective because it is still immature and starved of data. This is something they must improve immediately to combat these millions of violent Hebrew posts online.

Another direct point also mentioned by the BSR due diligence report is to edit and develop Meta’s Designated Organizations and Individuals (DOI) policy for terrorist entities, which accounts for most of the Palestinian content censorship. Although this policy has changed a little bit, by replacing “praise” with “glorification" for example, it still doesn’t meet the recommendations. Most if not all of the Palestinian media outlets that only cover news are restricted because many Palestinian symbols and leaders are designated as terrorists, as well as all political parties. So we request that Meta should engage with civil society in Palestine and Israel along with experts to change the policy to allow for freedom of expression.

Is there a particular challenge that you see to any of the recommendations that is making it difficult to move forward?

Our experience with Meta is not that good, maybe because the actors who wish to stifle discourse on Palestine and silence Palestinians online have more influence over the company policies. In the case of defending Palestinian digital rights, there is no independent state, therefore the responsibility of this struggle is undertaken by Palestinian civil society organisations like 7amleh and pro-Palestine activists, who in this case are less influential within these power dynamics at the company.

For example, recently there has been debate about the word shaheed, which means martyr in Arabic. It has a cultural aspect; for example, if someone was hit by a car and died, Palestinians call them a martyr. But this word is banned on Meta’s platforms because they consider only the political aspect. In 2023 there was a discussion and Meta was open to examining the issue, but still they haven’t done anything. There is progress sometimes, even on Meta’s side, but it’s very slow.

Since Elon Musk took over X (formerly known as Twitter), they dissolved the Trust and Safety Council and haven’t talked with civil society organisations but they changed a lot of policies. Now it has more space and freedom in terms of expressing Palestinian narratives but still we have an issue with violent content because it’s generally not moderated well.

How can civil society organisations around the world support this work and advocate for change?

As a Palestinian organisation, we have firsthand data and extensive documentation, we do advocacy and we also produce a lot of analysis and reports, gathering data through platforms like 7or. It’s not only for use in our advocacy and for raising awareness but can also be used by other groups. Organisations in Europe and the US, for example, can have more impact on legislators, decision makers and companies, whereas sometimes we have a problem in accessing the decision-making spaces. Outside organisations can do a lot with the data we provide to advocate, make recommendations and apply pressure for change. This advocacy effort is not enough if it's done by 7amleh alone without the support of like-minded organisations that believe in human rights for all.

Read the #Hashtag Palestine 2023 report by 7amleh in its entirety.

On Wednesday, 6 March 2024, IFEX, 7amleh, Palestine Center for Development and Media Freedoms (MADA) and APC are co-organising a webinar on the theme, "The Silencing Act: Journalism in Palestine". Find out more and register for the online event.