Introduction

What are digital rights?

We can define digital rights as (human) rights exercised in digital spaces or environments. This would imply the direct application and transfer of human rights as defined under resolutions such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in order to uphold the dignity and equality of people everywhere, including online spaces.

Digital or online spaces themselves do not refer only to internet spaces such as social media platforms and forums like Facebook, Twitter or Instagram or online marketplaces, blogs and personal websites, but also to environments that facilitate interactions between people and technology. This could include applications such as smart fridges, fitbits, surveillance cameras and biometrics software.

"Digital or online spaces themselves do not refer only to internet spaces such as social media platforms and forums like Facebook, Twitter or Instagram or online marketplaces, blogs and personal websites, but also to environments that facilitate interactions between people and technology."

While the term “technology” itself is often used interchangeably with “digital”, it’s important to note that digital technologies are also a type of the many forms of technology in use today. So, while the term “digital” might be misleading, a more useful way of looking at the kind of rights we are referring to is to think about all the types of human rights activated or made relevant as a result of our known and unknown interactions with digital technology.

Challenges

Today, some of the biggest challenges to digital rights include censorship by governments as well as internet platforms. For instance, in 2019, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) reported that from 2016 to 2019, over twenty (20) African countries had ordered network disruptions preventing people from those countries from accessing popular social media sites and in some cases, preventing SMS as well as mobile money functionalities. Similarly, all over Africa, there have been various attempts, some successful and others not, to pass bills directly limiting free speech in online spaces either by forcing social media users and platform owners to register or criminalising dissent by recharacterising it as a threat to national security. Social media platforms themselves in a bid to discourage the spread of hate speech and misinformation, have begun to rely more on automated filtering tools. However, these tools have been described as exceptionally prone to false positives. This means that automated tools incorrectly tag content as violence or misinformation when it may not be. Thus, automated content moderation developed by technology companies may not be very proficient, thereby unfairly restricting free speech.

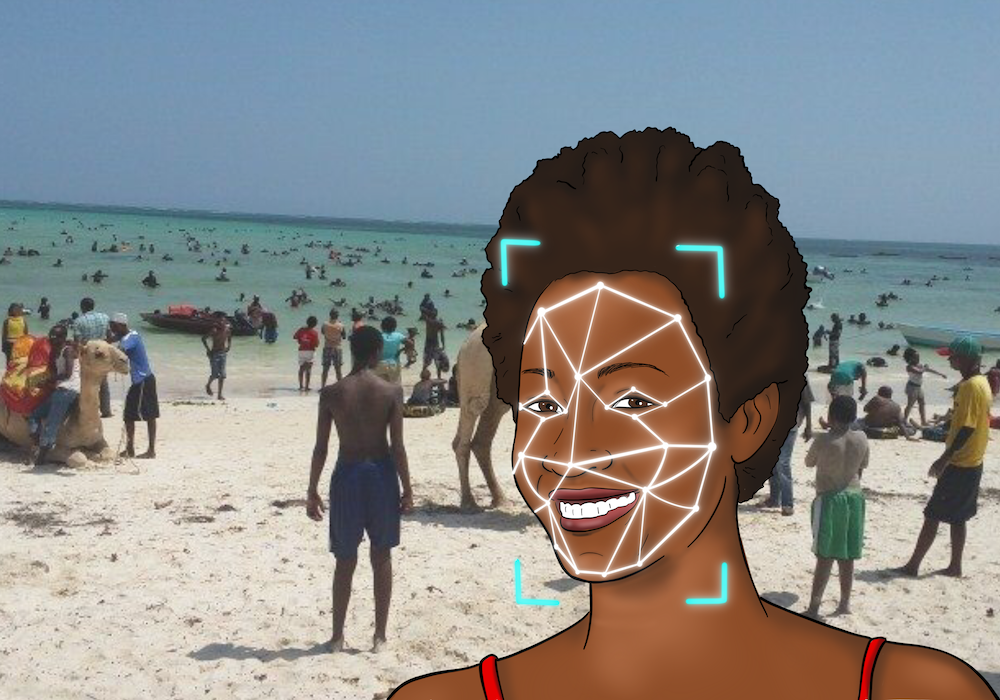

Another challenge to digital rights today is an increase in the use of facial recognition and other mass surveillance systems to monitor people. This constitutes a breach of privacy as well as dignity. Facial recognition systems themselves have been observed to often inaccurately identify black people leading to wrongful incarceration and arrests. These systems create a chilling environment for democratic freedoms and prevent people from exercising their digital rights online and often criminalising these very rights.

The inability of many people today to access the internet via mobile devices or computers also constitutes a deterrent to the full realization of digital rights. This issue is contributed to by infrastructural, economical as well as cultural factors.

The positive impact of technology for women

Image of woman in orange tshirt, kitenge wrapper and purple hijab smiling while looking at something on her smart phone. She is at the market. Image Credits: Neema Iyer

For many women, the advent of technology such as the internet is a new avenue and opportunity to engage in discourse and to advocate for their needs. Technological advances offer huge platforms without (m)any of the socio-cultural restrictions constructed against women as well as numerous opportunities to challenge them. As the rise of digital activism reveals, the internet makes consciousness-raising for important issues that particularly impact women easier to accomplish. Women use these spaces to express their individuality and creativity, to grow their careers and businesses as well as keep in touch and form new connections.

Technology innovations offer various solutions to women and assist them in carrying out day-to-day tasks. The application of technology to many sectors and industries has created many helpful portmanteaus such as fintech, healthtech, retailtech, edtech, agritech solutions which help many women around the world today accomplish tasks more efficiently.

Online safety

Online spaces often harbour and perpetuate threats to the experience of women participating in them. Women are disproportionately impacted by online violence such as image-based sexual abuse, non-consensual distribution of intimate images, as well as online scams and hacks. Women have been noted to be twice as likely as men to have their intimate images shared without their consent. A lack of a gendered-approach to online aggravation and crimes making it difficult for women to seek help from public and private authorities.

A 2020 report by Plan International featuring 14,000 girls and young women from 31 countries revealed that 58% of participants have been harassed or abused online. Similarly, findings from our 2020 report, Alternate Realities, Alternate Internets, revealed that 1 in 3 women interviewed in our five research countries across Africa had experienced some form of online gender-based violence, with sexual harassment constituting 36% of online violence experienced.

Misinformation, Disinformation and Mal-information

Misinformation, disinformation and mal-information are also examples of threats to women’s digital experiences. While misinformation refers to the sharing of false or misleading information, disinformation refers to the use of misinformation deliberately and mal-information is the use of true, correct information to inflict harm.

Misinformation, disinformation and mal-information are forms of online violence that are disproportionately gendered in nature and which more often target high profile women in politics, journalism and women’s rights activists to discredit them.

These attacks are often sexual in nature, may utilise synthetic forms of media such as deepfakes and often use an array of personalised attacks on the sex and sexuality of the intended victims. Information as a form of violence often plays to already existing stereotypes or fears and passes them off as the truth. As a result, misinformation, disinformation and mal-information pose serious threats to democratic institutions today.

Accessibility

Image of a toddler in a mint colored dress, playing with a tablet. Image Credits: Neema Iyer.

According to the International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU) 2019 report, only 48% of women use the internet, compared to 58% of men globally. The report also states that the proportion of women using the Internet is higher than that of men in only 8% of countries, with gender equality in internet use only found in just over one-quarter of countries. Some other analysis such as that of the Web Society also reveals that men remain 21% more likely to be online than women, a number rising to 52% in the world’s least developed countries (LDCs).

The GSMA report on the Digital Gender Divide places the mobile gender gap in Sub-Saharan Africa at 37%, a number reputed to be the second-highest in the world.Some of the factors hindering the accessibility of the internet to women flow from cultural, economic and infrastructural barriers boiling down to time, affordability, digital skills, service quality and availability restrictions. The digital gender divide is therefore also tied to the gender pay gap as well as the glass ceiling. Women, who are very often the primary caregivers in their homes are expected to perform unpaid domestic labour which eats into their time and income leaving them with no means or opportunity for online participation. Biases inherent in technology development and deployment and culture also prevent women from being early users and adopters of technology.

Internet shutdowns

Some of the excuses which have been outlined as justification for internet shutdowns by governments include preventing cheating by students during national exams, to suppressing reporting, criticism or dissent during or around elections or protests and to banning the spread of news about terrorist attacks, even accurate reporting, in order to prevent panic and copycat actions.

Shutdowns have been shown to disproportionately affect minorities such as women, especially during the vulnerable periods that occasion them and they affect rural women at the intersections of poverty and gender. Ethnic minorities also feel a keen sense of exclusion during shutdowns.

A report on the effects of internet shutdowns of women in Manipur, India, listed economic losses, safety, freedom of speech, emotional wellbeing, no support from the state in the case of emergencies as some of the effects of lockdowns on women.

Internet shutdowns also affect activists who rely on the internet to network and communicate with local and international partners and sponsors as well as citizens. In an article by the Association for Progressive Communications, on the effects of internet shutdowns in Africa, Françoise Mukuku, a digital rights activist and former executive director of Si Jeunesse Savait, a DRC-based young women’s organisation described the feeling in the following words:

"It is like being cut off from the world. The frustration of not knowing when it will be back, topped up with the shame of having to call your friend in Europe, giving them your password so they can access your email on your behalf and retrieve the phone number of a very important contact. Almost in tears, because you can't meet your work deadlines."

A feeling of powerlessness and disconnect was how yet another respondent, Arsene Tungali, executive director of Rudi International described the shutdown:

"You call a friend to ask them whether they are able to connect to the internet, they tell you they wanted to call you as well to check. You then realise that the internet has been shut down and it's like you are going ten centuries behind, the world stops in front of you as you can no longer read your emails, cannot check your WhatsApp messages, cannot browse any other social media. It is so frustrating. You feel powerless and weakened by those who have power."

During a pandemic period, such as this, it is important for open communications systems to exist for health and safety. Digital platforms create opportunities for education and wellbeing on issues such as sexual and reproductive health and financial education that might otherwise be restricted to women and so while it might be possible for men and young boys to continue their schooling or trading, women are cut out and unable to do so.

Surveillance

Image of an afro-haired woman’s smiling face. On her face is an outline of the lines and dots used in facial regocnition technology. She is at the beach. Image credits: Neema Iyer

The use of surveillance systems by private individuals, very often male relatives and intimate partners as well as agents of the state to monitor the activities of women is a form of technology-facilitated violence – which is violence carried out with the aid of any form of technology, including but not limited to digital and online tech – against women that infringe on their digital rights. Worse, because women are often not very digital savvy, they might be unaware of the installation and usage of these devices as well as how to deactivate them.

Surveillance carried out on women is often couched as beneficial to the safety of women however, this breach of privacy has been long documented to be a form of violence against women used to control[18], coerce and force women into subordinate roles through agents of the public and private acting in concert in a patriarchal society.

Surveillance of women prevents free expression and does not permit women to be and act as free persons with individual freedoms.

Technology determinism

Technology determinism refers to the idea that technology (innovations), and not people, are responsible for cultural changes caused by technology on people as well as society. According to Ruha Benjamin, technology determinism places technology in the driver’s seat. At its core, technology determinism promotes the idea that technology is an autonomous force, and that the effects of its deployment and use, beneficial or not, are inevitable.

Applied to women’s digital rights, technology determinism works to ensure that often, technology-facilitated violence against women in online platforms are not blamed on the persons or groups who created or moderate such platforms, but rather on the platforms themselves. Digital violence is then merely an inevitable negative side effect which women should expect, and protect themselves from. In essence, technology determinism is used to blame and shame women for acts of violence committed against them.

In Africa, technological determinism has influenced discourses surrounding the implementation of ICT infrastructure. It is taken for granted in many cases, that ICT will transform the economies of many African nations and their citizenry. These discussions are often had without consideration for the class and gender factors that ensure that women are denied access to these technologies. This effect also spills over to the automation of low-skilled jobs which are often carried out by women. The mass adoption of automation by global economies in the desire for national economic growth therefore blindly ignores the impact on women putting their already hampered ability to participate in digital spaces at risk.

In Nigeria as well as other countries in Africa[21], the rapid growth of the fintech industry and the services they provide has led to the perpetuation of increasingly intrusive data collection practices for profit-making purposes, which are justified as an inevitable step in the actualisation of a digital society.

However, this could not be further from the truth as technology is not an autonomous force but one subject to tensions between various forces.

Movement building

How can feminist and women’s rights groups participate in digital rights movements?

Image of woman in blue headwrap, red shoal, and ornate jewellery looking into her smart phone. She is a women’s group meeting. Image Credits: Neema Iyer

The challenges women face in digital spaces today provide opportunities for feminist and women’s rights groups to participate, to collaborate and actively challenge tech-facilitated violence and advance the rights of women online.

While feminist and women’s movements are often conflated or used interchangeably to mean the same thing, feminist researchers have endeavoured to draw a line of distinction between them. One proposed definition is that women’s rights movements can be defined as a subset of sociopolitical movements with a focus on women’s gendered experiences. These experiences could be economical in nature, therefore supporting financial empowerment opportunities for women, political, so as to improve the visibility of women in the political space, and even nationalist in nature.

Another definition defines women’s movements to include even feminist and anti-feminist movements but outlines a distinction between women’s movements and women in movements, defining the latter to mean the participation of women in other social movements. Feminist movements are, however, primarily characterised by their challenge to patriarchal structures.

Women’s movements have been criticised for sometimes seeking to maintain traditional gender roles held by women, such as childbearing and homemaking. However, in spite of these critiques, women’s movements are extremely effective at driving attention to and promoting and advocating the rights of women in important sectors.

Many feminist and women’s groups today understand the value of organising online and in digital spaces especially through social media and messaging platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter. Digital rights movements, which encompass both activist movements that are merely spread and facilitated through online spaces as well as issues directly related to digital rights, can be ignited with hashtags. Examples of successful social media movements such as #MeToo, #EndSars, #BlackLivesMatter, #CongoIsBleeding, #ShutItAllDown, and #KeepItOnUganda powerfully illustrate how the human rights movement can be kickstarted and brought to the forefront online.

Awareness raising

Part of the groundwork done by feminist and women’s groups regarding issues that uniquely affect women is to raise awareness in local communities and at a regional or national level through town hall meetings with local leaders and women, outreaches to religious places of worship, schools and other public places. These activities could be aided by flyers, posters, drama presentations and speeches.

The goal of awareness-raising is to spread information and draw attention to the impacts of a practice, which in this case would be common practices that affect the digital rights of women.

While online awareness-raising is extremely useful, only working in online spaces could deceive and mislead activist groups about the effectiveness of their campaigns. The overall goal of awareness campaigns is ultimately to cause a shift in the collective consciousness of society. Fortunately, feminist and women’s movement groups have historically been successful at organising, both physically and virtually, to challenge the status quo.

In Uganda for instance, the Women in Uganda Network (WOUGNET), campaigned with the hashtag #SayNoToOnlineGBV during the 16 Days of Activism against GBV in 2020, along with Encrypt Uganda, DefendDefenders, Digital Human Rights Lab, African Defenders and Digital Literacy Initiative highlighting issues and cases of online GBV in Uganda. WOUGNET highlighted the identified forms of online gender-based violence to include: non-consensual intimate images, cyberbullying, online sexual harassment, doxing, cyberstalking, and impersonation.

Image 1: Screenshot of Women of Uganda Network’s #SayNoToOnlineGBV Campaign

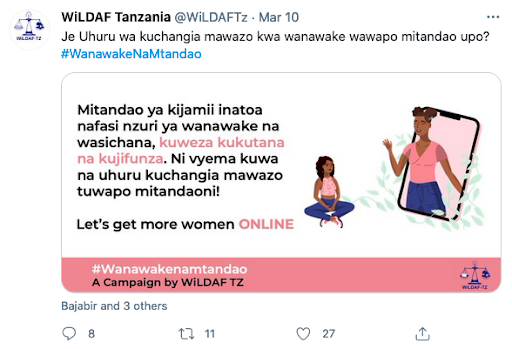

Image 2: Screenshot of WiLDAF-TZ #WanawakenaMtandao Campaign

During the same period, the Centre for Information Technology and Development (CITAD) organised a number of activities, both online and offline, on digital rights and risks and developed a lexicon for online violence for female students in secondary schools.

Advocacy and policy change

Very often, following successful awareness-raising campaigns and sometimes in consonance with them, women and feminist groups build on the shared knowledge to advocate for socio-cultural and legal change. Laws and policies need the support and agreement of the people to be successful and effectively carry out their intended goals.

Advocacy could also involve collaborating with other social justice groups to increase visibility and increase impact. The desired policy changes could begin from local government levels to state or regional levels before seeing a wide impact. It could also be the other way around and begin from the national level.

In the Benin Republic, Mylène Flicka, a Beninese activist working with other activists successfully fought to end the social media tax instituted by the Beninese government which would have decreased the number of active mobile broadband subscribers by 20%.

By creating petitions and hashtags, #TaxePasMesMo (Don’t tax my megabytes), as well as offline protests and sit-ins, Mylène and other activists and groups were able to successfully prevail on the Benin government to abrogate the tax. At Pollicy, we have designed a guide for organisations interested in digital rights advocacy.

Image 3: Screenshot of Mylène Flicka #TaxePasMesMo Call to Action

Supporting women in STEM

It is no news that despite the history of women in tech, with the first coder being a woman, Ada Lovelace and the valuable contributions of women programmers in the Second World War, today the tech industry is primarily male-dominated. Statistics show that 25% of Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft’s employees are female and only 37% of tech start-ups have at least one woman on the board of directors. The report also shows the ratio of men to women as 5:1!

An important part of promoting digital rights is by changing the homosocial environments that a majority of tech innovations are developed in. This can be done by supporting and encouraging young girls and women into STEM and STEM-adjacent fields. However, the job doesn’t end there. It has been shown that 41% of women in STEM quit their jobs while just 17% of men do so. Supporting women in STEM is a continuous process that involves a multitude of stakeholders to ensure that the women who do get into the field stay and flourish well enough to encourage other women.

One example of such a network is WanaData, a Pan-African network of female data scientists and scientists using data journalism to change the landscape of news reporting in Africa. Yet another successful example is Django Girls, a global non-profit organization and a community that empowers and helps women to organize free, one-day programming workshops by providing tools, resources and support. Since 2014, Django girls events have been held in 534 cities in 98 countries.

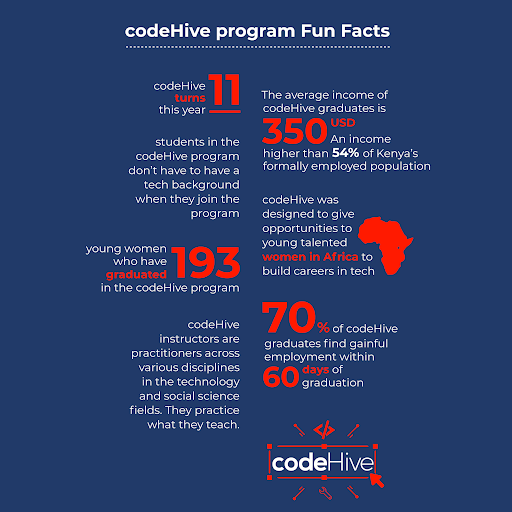

Image 4: Facts about AkiraChix’s codeHive Program based in Nairobi, Kenya

Data and digital literacy initiatives

While not all women can – or should! – go into STEM fields, today’s digital world makes it important for everyone to have digital and data literacy skills. It is important for women to be able to communicate and build worlds of their own imaginings digitally. In order to take control of their digital lives, women also need to be able to control or at the very least monitor their data streams to ensure it is used for beneficial purposes.

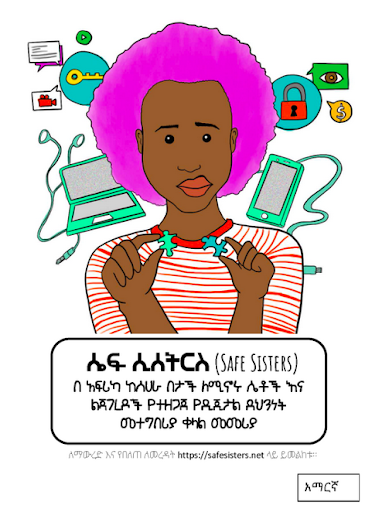

Successful programs training women in digital security include Safe Sisters, a fellowship program that trains women human rights defenders, journalists or media workers, and activists to understand and respond to the digital security challenges they face in their work and daily life. Cyberwomen and Tactical Tech’s Gender and Tech Resources Wiki are other examples of programs with digital security curricula aimed at offering trainers with tools to provide in-person learning experiences to human rights defenders and journalists working in high-risk environments.

By collaborating with these groups, feminist organisations are able to share relevant gender-specific experiences as well as data and advice for lasting impact.

Image 5: Safe Sisters Digital Hygiene Guide in Amharic

Resources

- Introduction to digital rights

- Online gender-based violence

- Digital security guides

- Platform governance

- Artificial intelligence

- Miscellaneous

Cited Materials

- “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” United Nations, accessed February 23, 2021, https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

- CIPESA, Digital Rights in Africa- Challenges and Policy Options (Kampala: CIPESA, 2019), 5, accessed February 23, 2021, https://cipesa.org/?wpfb_dl=287.

- Sophie Maddocks, “‘Revenge Porn’: 5 Important Reasons Why We Should Not Call It By That Name,” last modified January 16, 2019, https://www.genderit.org/node/5232/.

- “Know the Facts about Women Online,” eSafety Commissioner, accessed February 22, 2021, https://www.esafety.gov.au/women/know-facts-about-women-online.

- Plan International, Free to be online? Girls’ and Young Women’s Experiences of Online Harassment (Plan International, 2020), 2, accessed February 22, 2021, https://plan-international.org/publications/free-to-be-online/.

- Pollicy, Alternate Realities, Alternate Internets (Kampala: Pollicy, 2020), 47, accessed February 23, 2021, https://ogbv.pollicy.org/report.pdf.

- “Understanding Misinformation, Disinformation and Malinformation” (infographic), Tech Hive Advisory, November, 2020, accessed February 23, 2021.

- Stabilisation Unit, Quick Read-Gender and countering disinformation (London: Stabilisation Unit, 2020), 1, accessed February 23, 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo….

- Rana Ayyub, “I Was The Victim of a Deepfake Porn Plot Intended to Silence Me,” Life Less Ordinary (blog), HuffPost UK, November 21, 2018, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/deepfake-porn_uk_5bf2c126e4b0f32….

- “Gendered Disinformation, Fake News, and Women in Politics,” Council on Foreign Relations (blog), December 6, 2019, https://www.cfr.org/blog/gendered-disinformation-fake-news-and-women-po….

- “The Digital Gender Gap is Growing Fast in Developing Countries,” ITU, accessed February 23, 2021,

- “The Gender Gap in Internet Access: Using a Women-Centred Method,” Web Foundation (blog), March 10, 2020 https://webfoundation.org/2020/03/the-gender-gap-in-internet-access-usi….

- GSMA, The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2020 (London: GSMA, 2020), 30, accessed February 23, 2021, https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/GS….

- “Internet Shutdowns, Gender, Net Neutrality, and more at the United Nations,” Access Now, June 6, 2017, https://www.accessnow.org/internet-shutdowns-gender-net-neutrality-unit….

- S. K. Chinmayi and Rohini Lakshané, Of Sieges and Shutdowns (Bangalore: The Bachchao Project, 2018), 36, accessed February 23, 2021, http://thebachchaoproject.org/wp-content/uploads/Of_Sieges_and_Shutdown….

- “Internet shutdowns in Africa: ‘It is like being cut off from the world’,” Association for Progressive Communications, last updated July 22, 2019, https://www.apc.org/en/news/internet-shutdowns-africa-it-being-cut-world.

- Deborah Brown and Allison Pytlak, Why Gender Matters in International Cyber Security (Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the Association for Progressive Communications, 2020), 10-12, accessed February 23, 2021, https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/Gender_Matters_Report_Web_A4.pdf

- General Assembly resolution 48/104, Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, A/RES/48/104 (20 December 1993), available from http://www.un-documents.net/a48r104.htm.

- Crystal Dicks and Prakashnee Govender, Feminist Visions of the Future of Work: Africa (Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2020), 8 – 9, accessed February 23, 2021, http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/15796.pdf

- Tech Hive Advisory, “Digital Lending: Inside the Practice of LendTechs”, LinkedIn, February 19, 2021, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/tech-hive-advisory_digital-lending-insid….

- Francis Monyango, “Mobile Money Lending and AI: The Right not to be Subject to Automated Decision Making,” Global Information Society Watch, March 24, 2019, https://www.giswatch.org/node/6177.

- Amanda Gouws, “Unpacking the Difference between Feminist and Women’s Movements in Africa,” Conversation, August 9, 2015, https://theconversation.com/unpacking-the-difference-between-feminist-a…

- Karen Beckwith, “Beyond Compare? Women’s Movements in Comparative Perspective,” European Journal of Political Research 34, no. 4 (2000): 437–438, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00521.

- Sandra Aceng, “Online GBV – Why it’s Still Crucial to Raise Awareness,” Digital Human Rights Lab (blog), December 15, 2020.

- “Raising Youth Awareness and Seeking Support for ‘Policies That Favour a Feminist Internet’: Taking Back the Tech With CITAD,” Take Back The Tech, https://www.takebackthetech.net/node/6781

- Christoph Stork and Steve Esselaar, When the People Talk: Understanding the Impact of Taxation in the ICT Sector in Benin (Washington DC: Alliance for Affordable Internet, 2019), 3, accessed February 23, 2021, https://1e8q3q16vyc81g8l3h3md6q5f5e-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/….

- “Here’s Your Guide to Conducting Digital Advocacy,” Pollicy (blog), Medium, September 29, 2020, https://pollicy.medium.com/heres-your-guide-to-conducting-digital-advoc…

- Darina Lynkova, “Women in Technology Statistics: What’s New in 2020?,” Tech Jury (blog), January 22, 2020, https://techjury.net/blog/women-in-technology-statistics/.

- “About Us,” WanaData (blog), Medium , April 11, 2019, https://medium.com/wanadata-africa/about-us-a4c53027b716.

- Django Girls (website), accessed February 23, 2021, https://djangogirls.org/.

- Safe Sisters (website), accessed February 23, 2021 https://safesisters.net/.

- Cyberwomen (website), accessed February 23, 2021, https://cyber-women.com/.

- Gender and Tech Resources (website), accessed February 23, 2021, https://gendersec.tacticaltech.org/wiki/index.php/Main_Page.

- “Internet Freedom Festival,” Civil Rights Defenders, March 13, 2018, https://crd.org/2018/03/13/internet-freedom-festival/