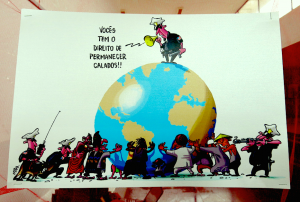

«You have the right to stay silent». Poster exposed the 2015 WSF in Tunis.After having been held in silence and fear for years, public debate has been flourishing in Tunisia since 2011. Tunisian journalists Sana Sbouai and Lilia Weslaty actively participate in the day-to-day struggle to develop free alternative media. This is their account of the current situation.

«You have the right to stay silent». Poster exposed the 2015 WSF in Tunis.After having been held in silence and fear for years, public debate has been flourishing in Tunisia since 2011. Tunisian journalists Sana Sbouai and Lilia Weslaty actively participate in the day-to-day struggle to develop free alternative media. This is their account of the current situation.

Achievements of the revolution: The outbreak of voices and opinions

Since the revolution in Tunisia, freedom of expression has certainly emerged as one of the greatest victories. “Even though they sometimes express themselves recklessly and indiscriminately, people are talking. They are now free to speak and denounce and they value this freedom. There have been multiple attempts to restore censorship, but none has succeeded,” explains Sana Sbouai, editor-in-chief of independent media outlet Inkyfada.

With this newly acquired freedom of speech, a great deal of work is still needed to break down the structures and behaviours shaped by years of tyranny. While citizen journalism has experienced spectacular growth, the majority of the mass media remain in the hands of former leaders of the Ben Ali regime or big economic interests. The perpetual question of financing frequently hampers the surge in new projects carried out by activists or citizens who have the desire to offer alternative media coverage. According to Lilia Weslaty, an independent journalist and human rights activist, even if there has been an explosion in new media projects, there is a lack of genuine independent opposition media. “A lot of media are still at the commenting and blogging stage even though Tunisia has a serious need for professional journalism, relevant coverage and investigation,” she explains. In order to remedy the situation, Weslaty has short-term plans to create a new independent media project that would provide in-depth coverage in combination with a strict journalistic ethic.

Tunisian media are walking a tightrope

However, freedom of expression and press freedom in Tunisia are at risk. For the past few months, freedom of speech, opinion and press and internet rights are being debated in Tunisia in the context of the adoption of a new anti-terrorism law. Even though details of the bill have not yet been published, many fear a return of censorship and surveillance.

With the “terrorist threat” message hammered on by different countries that have adopted anti-terrorism laws, populations are confronted with changes in security policies and media teetering between the freedom of coverage of events and the risk of manipulation. “Most of the time, when we witness ‘terrorist’ events, the assailants are killed,” explains Sana Sbouai. “And a dead suspect is an ideal convict because he cannot defend nor explain himself. When one has access to a single version of the facts given by the authorities, it is very difficult to find other sources to cross-check information, and we can easily fall into protectionist propaganda.” Beyond Tunisia, journalists from all over the world are facing the same question: how can we provide honest and equitable coverage of security issues? According to the editor-in-chief of Inkyfada, the issue is even more thorny in Tunisia as journalists are still learning the profession.

The proposed new anti-terrorism law is not the only measure which worries advocates of digital rights. In a report published last June, Reporters Without Borders expressed their concern regarding the powers granted to the Technical Agency of Telecommunications (TAT) created by Decree 2013-45062. “The new TAT’s role is to provide technical support to the investigations ordered by the judiciary power for ‘crimes on information systems and communication’. However, the agency’s capacity to deal with such cases is ambiguous and has ignited fear of a return to the practices of the old regime, including the systematic surveillance of citizens and the distortion of procedures of conviction which do not respect the rights of the defense,” states their report.

Nawaat, an independent Tunisian media outlet, also reported that “in the aftermath of the deadly attack of Henchir El-Talla, the same day as the launch of the anti-terrorist crisis unit, the Minister of the Interior announced the implementation of the TAT which would allow it to not only ‘hunt down and block terrorist websites’, but also to ‘indict their users’.” This statement suggests that the monitoring performed by the TAT and the new anti-terrorist law could lead to the establishment of measures preventing journalists and bloggers from reporting on issues related to security and terrorist networks.

Even if several groups in Tunisia fear excesses, Sana Sbouai remains positive and believes that the government will not go so far as to attack the free press. “It is difficult for governments to take direct action against journalists because there will be an outcry,” she believes. “When freedom of media is threatened, it represents a societal regression. It is indeed the only freedom which has been fully acquired in the revolution.”

In a context where activists and journalists face a pervasive threat, Sbouai and Weslaty have both had to secure their use of the internet and the different means of communication they use in order to perform investigations. By working with a mature network of “hacktivists” who fight to preserve a free internet, Sbouai and Weslaty are able to protect their sources in a context where no one really knows who’s being watched.

A huge step forward since the dictatorship

During the 24 years of dictatorship under the Ben Ali regime in Tunisia, due to censorship, control of speech, fear and suppression of criticism of the regime, few people dared to talk about the political situation or about the repression of human rights. Those who dared to do so were hunted down, monitored, intimidated. For Weslaty, professional journalism had never been a dream nor an ambition. This role imposed itself quite naturally when she decided to break the silence by denouncing what was going on in her country and community. In 2009, she began to write and share her analysis, criticism and views of what was happening in Tunisia.

While sharpening her pen on Facebook and on forums, she attempted to set the record straight by comparing the political and media discourse with what was really going on. For Weslaty, journalism and activism have been interrelated from the beginning, in order to aim the pen where it hurts. “I did not have a blog because any blog was automatically censored, so I was using Facebook or Twitter. People could read my pages, but they were almost all censored. And I had to change names several times and add https so that people could access them. Each time it was a war against the system,” she explains.

Exposing and challenging a corrupted system which puts its population at risk is not an easy thing, particularly in a repressive context. As her work became inseparable from her day-to-day life, Weslaty lived in constant doubt and uncertainty before the revolution. “I had to move time and time again and I never gave away my address,” she remembers. “I knew that there was always a risk of being subjected to torture or even death.”

A new media landscape is currently under construction in Tunisia. The journalists and citizens working towards its creation will have to stay the course despite looming challenges in the years to come. To do so, they will need support and solidarity from the international community.

For more information and a comparison of the old and new anti-terrorism law in Tunisia (french): https://inkyfada.com/2014/06/reforme-loi-anti-terroriste-tunisie/

[Isabelle L’Héritier met and interviewed Sana Sbouai during the World Social Forum in Tunis, a few days after the attack at the Bardo Museum.]