This piece was originally published by APC member organisation EngageMedia.

This article is part of Pandemic of Control, a series of articles that aims to further public discourse on the rise of digital authoritarianism in the Asia-Pacific amid COVID-19. Pandemic of Control is an initiative by EngageMedia, in partnership with CommonEdge. Read more about the series here, and about the contributing writer at the end of this piece.

In 2003, Susan Sontag published a book-length essay Regarding the Pain of Others, a powerful meditation on the representation of distant sufferings.1 For Sontag, images of war-torn bodies, smashed houses, and starving children, brought straight to our living rooms via modern media, created a culture of spectatorship that simultaneously allows us to witness and glance away from the trauma of others. She wrote: “Information about what is happening elsewhere, called “news,” features conflict and violence […] to which the response is compassion, or indignation, or titillation, or approval, as each misery heaves into view.” What Sontag addressed in Regarding the Pain of Others remains timeless, insofar as she reminds us of the power of technology to alter how we come to understand distant sufferings, and how we think those sufferings ought to be addressed.

Twenty years on since Sontag’s powerful critique, we are now supplied with countless opportunities not only to witness others’ suffering, but also to remotely provide aid and assistance. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, platforms that connect local citizens who are willing to help each other have emerged and thrived in Vietnam amid the lack of a proper welfare regime. Launched during the country’s strict August 2021 lockdown, these platforms were lauded as a timely, innovative, and humane technological solution to address the lack of basic necessities—food, medical care, shelter—needed to care for oneself and others.

But while these apps are touted as exemplars of tech for good, they may also engender new vulnerabilities and harms. Platforms to provide aid and protection can also function as a form of digital authoritarianism that limits perceptions of what counts as aid, and what it means to provide it.

Zalo Connect and the intermediation of Vietnam’s COVID-19 response

Vietnam had been hailed as a global COVID-19 success story until mid-2021, when the highly contagious Delta variant swept its largest metropolis, Ho Chi Minh City, and other southern provinces. Tough lockdowns were imposed and people were not allowed to leave their homes, even for take-away food. The urban poor in Vietnam have always relied on informal, more affordable food systems such as wet markets and street vendors, but these informal spaces were forced to close as they were deemed unhygienic and potential hotspots for virus contamination. For many precarious daily wage earners who couldn’t afford to stockpile food from supermarkets, starvation became a daily reality.

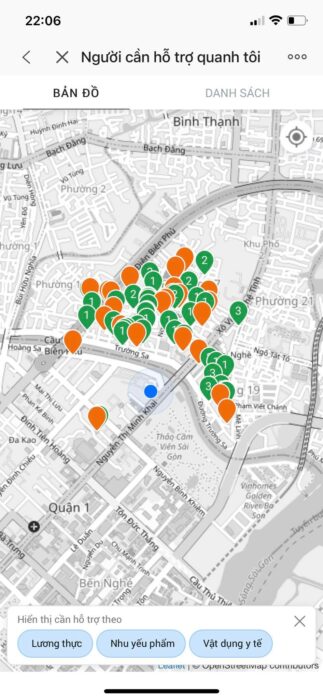

In partnership with the National Centre for Technology, Vietnamese private tech company VNG Corporation developed Zalo Connect, a new feature under the already popular networking platform Zalo that allows users to request emergency help and be matched with a donor willing to provide food, necessities, medical equipment, or medical advice. Zalo Connect’s interface also has a map view navigation that enables potential donors to locate nearby people in need. As the health crisis quickly spiraled into a hunger crisis, unsurprisingly 92% of the requests for support are reported to be food-related items.2

Zalo Connect’s interface translates the cityscape and the crisis unfolding within it into a set of orange and green dots, representing people who request emergency assistance. People who have not received any help are represented by orange dots. Once help is provided, the orange dot will switch to green and information on the number of times they have been assisted will be listed. By clicking on the dots, potential donors can see detailed information regarding vulnerable people’s circumstances as well as their specific requests. In only a fortnight since its launch, Zalo Connect reported 85,000 matches.

Zalo Connect exemplifies a humanitarian trend that centres on extracting data from vulnerable communities as a precondition for receiving aid, protection, and justice. How do these platforms perpetuate and legitimise the exploitative logic of data extraction where the beneficiaries are compelled to publish their own miseries in exchange for aid? What are the harms inflicted on these vulnerable communities as images, information, and other data representing their lives and bodies are stored in digital space—but over which they have no control? What is at stake when the pressing task of alleviating suffering during the crisis is framed as an issue of matching supply and demand?

The imperative of self-disclosing miseries: (Self) surveillance and the production of new vulnerabilities and harms

I was overseas when Ho Chi Minh City and its neighbouring provinces entered their strictest lockdown, taking my maternity leave to care for my two-month-old newborn. At the time, my friends in Vietnam occasionally sent me information about people needing emergency help to raise funds for them. Among many requests, I felt the urge to donate to a mother who just gave birth (perhaps because I was in a similar situation then); she was unable to breastfeed her child, yet could not afford baby formula. We sent her a message, and without us requesting any evidence, she immediately sent through all the hospital documents detailing every pregnancy check-up and a certificate showing the date and time of her recent C-section. She must have believed that she and her physical body could not speak with credibility, and that these forms of documentation were seen as more credible conveyors of her circumstances, no matter how intimate, personal, or traumatising they might be.

My encounter with the mother took place via another platform, but in many ways, it exemplifies the kind of social interactions mediated by Zalo Connect—where people in insecure situations are compelled to share information about their sufferings, trauma, and losses, in exchange for aid and protection. Aside from choosing a predefined category of assistance, those seeking aid are prompted to give specific details of their requests. Though not explicitly required by the platform, many people opt to narrate their miseries and hardship, perhaps in a bid to move potential donors. For example, a request reposted on an article about Zalo Connect read: “I need help with food. I’m working at a construction site. My husband passed away and I’m raising two children on my own. One is sick but we can’t afford surgery. And now I’m unemployed.”3

The issue then becomes one of autonomy and control. While the stories are clearly in the control of the persons they are seen to represent, the requesters depend on those stories to bring them aid—thus putting the onus on them to calibrate the kind of story capable of generating sympathy and compelling donors to take action. In other words, the seeming democratisation of access to aid afforded by Zalo Connect reinforces a self-surveilling regime, insofar as the agency and ownership of the story come up against the donor’s need for credible evidence and believable narratives.

The self-disclosure of miseries was compounded by contextual factors, such as social distancing measures, that prevented donors from traveling directly to donees’ residences and witnessing their plight firsthand.4 This distant witnessing creates a problem of trust, exacerbated by the pervasive discourse in popular media that seems to draw the line between the “deserving” and “undeserving”, “authentic” or “fake” poor. For example, an article from VNexpress featured a donor who was frustrated with many “fake” help messages she encountered, which was taking her ages to “verify” before deciding to help.5 She did not detail her method of verification, but we might imagine that this entails requesting more proof, more data, more documentation. The border between vigilance and surveillance can be dangerously thin.

Asymmetrical visibility: Reconfiguring relationships between the “helper” and the “helped”

The interface of Zalo Connect allows donors, the relatively privileged group, to look upon the cities as a whole and enclosed space; a place with many suffering bodies, but also as an entire place of kindness. Among many celebratory accounts of Zalo Connect, one succinctly puts it: “Zalo Connect allows for kindness to spread.”6

The map view of Zalo Connect also allows users to move smoothly from one scale to another so that users can see either the entire crisis-scape or at the minute level of an individual. In other words, potential donors are invited to see the crisis unfolding from the above: an all-seeing, all-knowing God’s eye view. We are not the object of surveillance; we are not the victims of many watching eyes.

Viewed in an optimistic light, the relative accessibility of mobile phones, the internet, and social media and their use in facilitating peer-to-peer aid may signal a bottom-up and localised distribution of support. While there is some truth to it, such an interpretation weighs too heavily on the democratic potential of technology. On the surface, there is seemingly no intermediation between donors and donees, just a smooth flow of information and exchange that provides transparency and an emotional bond. However, there is no way for a crisis-affected person to voice for themselves what they demand outside preconceived notions of aid. One media account, for example, described a beneficiary as “demanding”—she allegedly asked for high quality food as her child had a stomach issue—and tagged her request as “fake” simply because she didn’t fit the stereotype of “grateful donees” who would readily and enthusiastically accept whatever was given. As Theo Sowa, chief executive of the African Women’s Development Fund expressed: “When people portray us as victims, they don’t want to ask about solutions. Because people don’t ask victims for solutions.”7

In many ways, the saviour mentality is reproduced beyond the interface of the app; for example, the app is used as a part of a campaign to garner social capital for VNG, earning them more users and partnerships. The media landscape is replete with stories about how these vulnerable groups are grateful for the tool and the assistance they received. The vulnerable communities cannot turn back their gaze. Consequently, while Zalo Connect appears to give voice to otherwise voiceless communities, it is through this asymmetrical visibility and power relations that these communities are dehumanised. The exhibition of orange and green dots representing vulnerable bodies in crisis, oblivious to the diverse demands and needs these communities might have, is regarded only as someone to be seen, not someone (like us) who also sees.

By design, Zalo Connect does not allow for dignified access to aid. There is no framework to limit the amount and nature of the information that should be provided by the beneficiaries. Nor is there any consideration to destroying data about these vulnerable groups to protect their privacy. In a pandemic, this extra layer of extracting data from vulnerable communities in exchange for aid magnifies the power exercised over such communities, potentially resulting in shame, stigma, and retraumatisation. This also reconfigures new power relations over the most vulnerable communities that have already been more heavily surveilled under ordinary circumstances.

The power of problem framing: How platformising aid abstracts the issue from its systemic context

Zalo Connect illustrates how digital humanitarianism can function as a form of digital authoritarianism, legitimising an extractive relationship that requires a public disclosure of miseries with the very groups they seek to assist.

With each successful matching, the dots representing the beneficiaries switch from orange to green. We, the relatively privileged group, must assume these distressing situations have somehow been resolved. We must assume they have found some respite. But this bittersweet representation should not distract us from asking what harms are not being shown.

Difficult questions, therefore, need to be asked. What problems and solutions are being framed for us? Who benefits from this framing? What does it mean for how we calibrate vulnerability, aid, and protection? Against the context of persistent failure from the state to provide a safety net to its citizens, Zalo Connect’s design implies a transactional solution to a structural crisis: The donor sends food, necessities, or medical equipment, and the problem is solved. But the problem of providing the basic goods and services cannot be demoted into a mere problem of matching supply and demand.

References

1 Susan Sontag, ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’, Penguin Books, 2003.

2 Kim Lam, ‘Tính năng hỗ trợ người khó khăn do dịch bệnh Zalo Connect mở tại 20 tỉnh thành’ [Feature assisting vulnerable people due to the pandemic Zalo Connect launched in 20 cities], last modified 20 August 2021, Thanh Nien https://thanhnien.vn/tinh-nang-ho-tro-nguoi-kho-khan-do-dich-benh-zalo-connect-mo-tai-20-tinh-thanh-post1102796.html

3 Rosie Nguyen, ‘Zalo’s New Tool Boosts Mutual Aid During Vietnam’s Worst Covid Outbreak’, last modified 20 August 2021, Vietnamtimes,

https://vietnamtimes.org.vn/zalos-new-tool-boosts-mutual-aid-during-vietnams-worst-covid-outbreak-35080.html

4 This is how informal humanitarian assistance in Vietnam had been operating where a citizen would raise funds from their friends and families and travel to the fragile settings to give away their donations. With social distancing measures, all potential donors can see is self-narrated accounts of suffering on help-matching platforms.

5 Luu Quy, ‘Tìm người hỗ trợ nhu yếu phẩm qua Zalo [Locating people in need through Zalo], VNExpress, last modified 17 August 2021, https://vnexpress.net/tim-nguoi-ho-tro-nhu-yeu-pham-qua-zalo-4341837.html.

6 Quoc Huy, ‘Đánh giá tính năng Zalo Connect: Tính năng mang đậm tình người, dễ dàng kết nối người cho và người nhận nhu yếu phẩm [Evaluating Zalo Connect: a humane feature, easy to connect helpers and the helped]’, The Gioi Di Dong, last modified 18 August 2021.

7 Jennifer Lentfer, ‘Yes, charities want to make an impact. But poverty porn is not the way to do it’, last modified 12 Jan 2018, The Guardian,

https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2018/jan/12/charities-stop-poverty-porn-fundraising-ed-sheeran-comic-relief