Republished with permission from APC member KICTANet.

On 11 August 2021, KICTANet held a virtual meeting to disseminate its new research report, Public Participation: An Assessment of Recent ICT Policy Making Processes in Kenya.

The research assessed the extent to which the public participated in three recent information and communications technology (ICT) policy and law-making processes. The three policies were the National Information Communications and Technology Policy of 2019, Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act of 2018 and Data Protection Act of 2019.

The research was conducted between September 2020 and October 2020 with selected respondents from various multistakeholder groups. Article 10 of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 enshrines the principle of public participation as one of the national values and principles of governance. However, the approach taken by state bodies in the ICT sector to facilitate public participation varies.

Key highlights of the report

As mentioned earlier, the report analysed whether public participation was meaningfully included in these policy-making processes. Moreover, the research looked at whether the multistakeholder approach was considered and the extent to which the three processes adopted this approach.

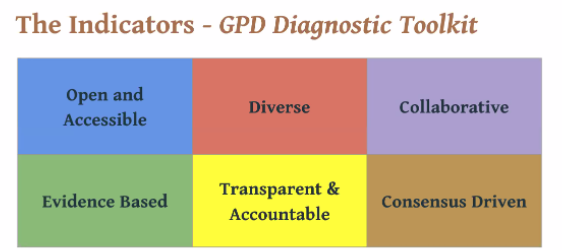

Victor Kapiyo, one of the researchers, stated that they used diagnostics tools to analyse the extent of public participation in the three ICT policies. They also reviewed if the processes were open, accessible, diverse, collaborative and consensus-driven, evidence-based, transparent and accountable.

Open and accessible

The Data Protection Act scored the highest in terms of openness and accessibility. This was attributed to the fact that there were multiple opportunities for stakeholders to engage in policymaking. Mr. Kapiyo noted that there was also high public interest in data protection and privacy issues, sparked by ongoing national events, such as the introduction of Huduma Namba and the global trend towards the adoption of national data protection laws following the adoption of the GDPR in the European Union. Moreover, county meetings were held and there was notable political will on data protection. The process for the Cybercrime Act, on the contrary, scored the least in openness and accessibility due to restrictions and limited opportunities for the public to make contributions. At the initial stage, it was shrouded with lots of secrecy. There was poor communication, poor representation of stakeholders and insufficient time and notices to allow the public to make contributions.

Diverse

Again, the process for the Data Protection Act ranked as the most diverse of the three processes because there was input, buy-in and support from diverse stakeholders through county forums and various opportunities to contribute offline and online. On the other hand, the process for the National Information Communications and Technology Policy ranked lowest in diversity. It was marked by failure to publish stakeholder input, poor documentation, poor feedback and limited participation of stakeholders.

Collaborative and consensus-driven

Here, the the process for National Information Communications and Technology Policy scored the highest because it was stakeholder-driven. It was deliberate and was marked by a collaborative bottom-up approach. Ms. Sigi Mwanzia, who also participated in the research, highlighted that this was due to the pressing need and demand from ICT stakeholders. They have called on the Ministry of Information, Communications and Technology (MoICT) to update the 2006 Policy, which had not been updated for almost eight years, despite global technological developments and national ICT sector changes in Kenya.

In terms of collaborative and consensus-driven, the Cybercrime Act process ranked the lowest. This is because of a disjointed approach, redundant government agency processes, closed-door engagements between government agencies and partners, poor collaboration and power imbalances.

Evidence-based

The research showed that for evidence-based processes, the process for Data Protection Act scored the highest while the process for the Cybercrime Act scored the lowest. The policy-making process for the Data Protection Act promoted a balance of expertise and research as well as the use of evidence and facts. The process for the Cybercrime Act had limited expertise and research, capacity gaps, special interest and neglect of stakeholder views.

Transparent and accountable

Again, the process for the Data Protection Act ranked highest in transparency and accountability, while the Cybercrime Act process ranked the lowest. At the time of research, the process for the Data Protection Act had clear stakeholder representation, clear documentation of contributions and clear engagement procedures.

“For example, the Communication Authority still hosts stakeholders’ submissions on its website whereas the National Assembly ICT committee report contains copies of stakeholders input submitted during this process,” added Sigi.

The Cybercrime Act ranked lowest due to opaque, closed and redundant processes and lack of a clear road map. Also, it was marked by the secrecy of bills, reports and processes. To date, there are no publicly available reports.

Key recommendations

The report made the following recommendations:

- The government should put in place a holistic, multidisciplinary and multistakeholder mechanism for public participation.

- The government should update and enact the Public Participation (No. 2) Bill of 2019.

- The government should provide at least twenty-one (21) days’ notice for public participation.

- The government should proactively engage more "non-traditional" stakeholders.

- The government should recognise that policy making requires collaboration and establishing a common purpose and goal with stakeholders.

- The government should conduct extensive, objective and evidence-based research and make it publicly available prior to developing policies and laws.

- In partnership with stakeholders, the government should prepare and publish guiding documents outlining formal procedures and mechanisms prior to developing policies and laws.

Participants' recommendation

Reacting to the research recommendations, participants at the dissemination session also shared their input. Mr Ephraim Percy Kenyanito highlighted the need for a clear roadmap in public participation, clear process and sources of funding and improved data protection process in future similar ICT policy processes. Ms Riva Jalipa observed that the Cybercrime Act had the most pain points. The Act was also problematic because the process was opaque and yet diverse expertise is necessary in contributing to the law. Riva recommended the need for the Cybercrime Act to be broad so that it can foresee and regulate future behaviour. Regarding the Data Protection Act, John Walubengo noted that Kenya has made a lot of strides when it comes to the National ICT Policy process. He added that the act remains one of the best guidelines we could adopt because the process consulted a diverse set of stakeholders and it had a clear timeline for the entire process.

Conclusion

Public participation in the ICT policy process must be open, accessible, diverse, collaborative, evidence-based and transparent. Also, the government needs to have a holistic, multidisciplinary and multistakeholder mechanism for public participation.

Download the full report here.